Before our Attention Was a Commodity: Memories of a Pre-Web Internet

2025-05-04What happens when kids grow up with powerful technology they’re not allowed to understand? We risk creating a digital world with few true digital natives. How public terminals, old Macs, and a programming teacher shaped my political imagination and tech skills.

I sometimes think back to the fact that few people my age or younger experienced the pre-web Internet or remember the transition to our current corporate model. I only remember it because I was a geeky kid without a computer at home, so I spent a lot of time at Vanderbilt University, where my dad was a grad student. That would’ve been late 1990 or early 1991, soon after my family moved from Canada to Nashville. I was about to start middle school.

Squatting the Vandy Labs

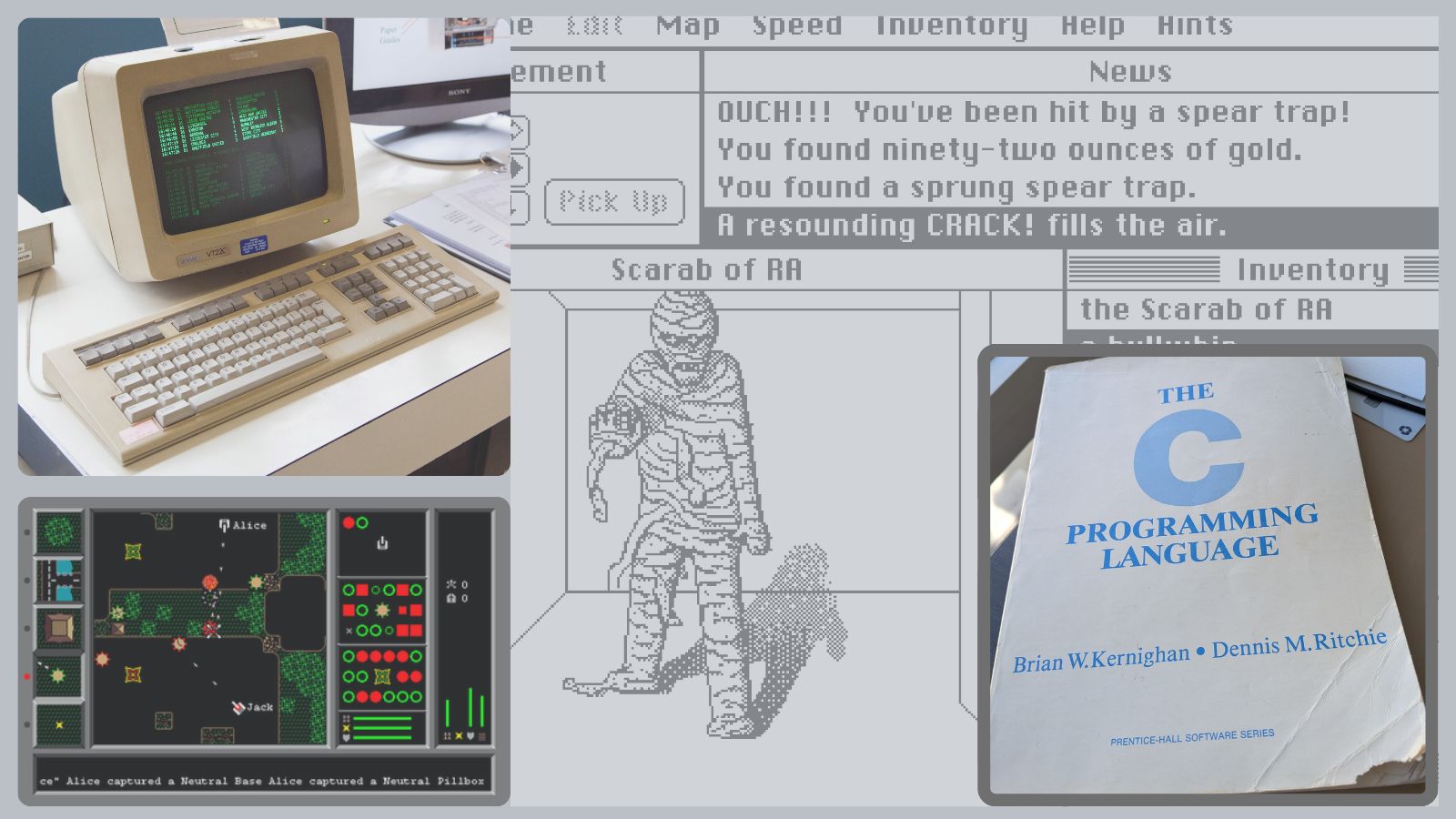

Back in Ontario, I pushed around a little cart and set up overhead projectors as part of the AV club, but I didn’t get a chance to use a computer. At Vandy, though, I got to play Tetris, Nibbles, Scorched Earth, and Scarab of Ra whenever I scored a public Macintosh or PC at the university library or lab. Otherwise, it was yellowing VT100 terminals with green or amber monochrome screens, which I was just as happy to occupy. I remember jumping up in fright at the mummy, loving the colors of VGA graphics and learning to ignore the glares from patrons annoyed at the kid monopolizing one of the few public computers.

These were the pre-AOL, pre-Eternal September days. I dialed into BBSes or logged into the local mainframe. I can still remember the FTP servers I used to find shareware and freeware games, the Usenet groups I followed to get tech support, and the VAX/VMS version I used to teach myself the command line. I started hearing about a new OS called Linux through Usenet groups and a couple of kids in the chess club, but without a computer at home, I didn’t pay much attention to it.

Turbo Pascal and Mrs. Brown

I started playing around with QBASIC a couple of years after this, but I got really lucky when I got to take a computer programming elective in my formerly-segregated magnet high school. I was the only Mexican kid in the school, and definitely the only one in the class. Mrs. Brown taught me structured programming concepts by writing out Turbo Pascal programs on paper, then typing and compiling them on shared IBM PCs. It was like a superpower to a kid like me, being able to see my thoughts come to life on those old screens. I tried to do the same on the central VAX, but even with the technical manuals, it wasn’t easy.

Then came Mosaic and graphical interfaces. Gopher servers were abandoned and telnet MUDs emptied out. I kept using Usenet for a while longer, but not by much. I finally got a computer at home in 1994, a Mac Quadra 610 to lay out my dad’s doctoral thesis in PageMaker , and the command line mostly exited my life until 1999, when I installed Linux/m68k on a then-ancient Mac IIci.

Once I had the Mac, I dived deep into ResEdit and HyperCard, pieces of software long obsolete. I taught myself C using CodeWarrior and the first edition of K&R’s The C Programming Language, a book I still have—complete with guinea pig bite marks. Three decades later, C remains my proverbial systems hammer for every technical nail I encounter. What I had learned helped me cajole my way into a two-period school aide position my senior year. I turned the room behind the school library into a hidden Mac computer lab decked out with an AppleTalk network. Bolo games over the local area network became a staple of 4th and 5th period. I saw my first banner ad on Yahoo! around this time, an omen of what the Internet would become.

Access Politics

I didn’t stick with engineering, but I wax nostalgic about these long-gone times. In hindsight, these technological experiences were also political: the central mainframe in a private university versus the old computers in a run-down public school. I certainly regret how much of that time and knowledge was locked into tools that corporations would later abandon, a feeling that informs my computing choices today and why I believe the future will ultimately be shaped by open source, non-corporate tools and systems.

I also can’t forget that many of these experiences happened because I had opportunities to teach myself and explore in spaces like university labs, library computers and my public school, the same spaces that are now under threat for many poor and immigrant kids, who might only have access to a locked down iOS device. A supercomputer in their palm but out of reach for tinkering and with few if any alternatives left for learning.

Those years shaped how I think about computers and systems. Not just as tools, but as spaces of learning, simultaneously political and technical. It seems that the kind of open, messy and public access to learning I enjoyed is rare these days. I’m grateful I got to experience it, but I’m also worried we will all lose if we don’t do something to expand these opportunities through public investment (every kid gets a Linux computer) and permissive access policies (easy sideloading in Apple hardware).

Today’s kids deserve the same opportunities I had growing up broke in the South during the 1990s—and I’m certain we’ll all benefit if they do, as they develop the next generation of systems and services.